Annelids (phylum Annelida) are bilaterally symmetrical worms which may or may not be segmented. The name “Annelida” comes from the Latin word "annellus", which means "little rings", as traditionally this phylum only includes segmented worms which mostly have a body made up of a series of identical segments, separate by ring-like constrictions (annuli). Recent phylogenetic studies, however, have shown that many unsegmented worms are genetically very similar to the annelids, and are in fact more closely related to annedids like earthworms than many marine annelids. These unsegmented worms are hence now placed under this phylum as well. As a result, there is no single external feature that can be used to differentiate annelids from other phyla.

Generally, the segmented annelids will have a body comprising identical segments (excluding the head and tail) containing the same set of organs, and in some cases, external structures used for locomotion. They should not be confused with arthropods like millipedes and centipedes, which will have segment legs that annelids lack. The above picture features an unidentified annelid worm.

The unsegmented annelids are believed to have lost the segments through evolution to better adapt to survive in their habitats.

Many annelids, except leeches, are known to be able to regenerate lost body parts, even their heads. A number of species can also reproduce asexually by splitting into two or several parts and regrow the lost parts. Some annelids can even regrow from severe damages, such as from a single segment! Most also reproduce sexually, and are mostly hermaphrodites with both male and female reproductive organs.

A) Earthworms (Class Oligochaeta)

Earthworms (subclass Oligochaeta) are possible the group of annelids that most Singaporeans are familiar with. The name "Oligochaeta" is means "a few (oligo) bristles (chaeta)", and the oligochaetes previously include the leeches, but studies have shown that the leeches should be placed on a separate class of their own. Earthworms are burrowing annelids which play important ecological roles in many terrestrial ecosystems. They aerate the soil as they burrow, and bring nutrients from underground to the surface. They also break down organic matter into humus to improve soil fertility, and is the prey of many animals, making them an important part of the food web. Their ability to regenerate lost body parts varies between species - some can grow into two new worms after they are bisected, while for others only one half will survive.

The above picture features an unidentified earthworm. Earthworms are generally hard to identified in the field, as specimens usually need to be examined under the microscope to check for the arrangement of the tiny hair-like structures to determine the species.

B) Leeches (Class Clitellata: Subclass Hirudinea)

Many people are familiar with leeches (class Clitellata: subclass Hirudinea) for their blood diet, but actually, most species feed on small invertebrates, and only some feed on blood. Depending on the species and habitat, the hosts of the blood-sucking species may be mammals, fishes, birds, reptiles or even snails. They detect their hosts by their odour, body heat or vibrations from their movements, and attach themselves to the latter with their sharp jaws in their mouth and strong suckers at the rear. They secrete an enzyme to prevent the blood from clotting, and drop off when they are full of blood.

The above photo features a Buffalo Leech (Hirudinaria sp.), which is sometimes encountered in freshwater habitats such as streams and ponds. Some marine leech species can also be found in Singapore, but the terrestrial species may have disappeared already due to the low mammal population in our forest.

C) Spoon Worms (Class Echiura)

The annelids include a few unsegmented worms, and the spoon worm (class Echiura) is one of them. Spoon worms are previously regarded as a phylum of their own, but recent phylogenetic studies showed that they are annelids. They are usually found in muddy or sandy substrates, though some species live under rocks too. They have a flattened proboscis (the whitish structure in the photo) which resembles a spoon on their front ends. They are usually filter feeders, and raising the proboscis out of their burrows to collect plankton and tiny organic matter.

The above picture features an unidentified spoon worm, which was found on a sandy-muddy shore.

D) Peanut Worms (Class Sipuncula)

Peanut worms (class Sipuncula) are previously regarded as a phylum of their own as well, but again, recent studies showed that they are also annelids. The body of a peanut worm comprises an unsegmented trunk and a retractable structure called an "introvert". When disturbed, they can retract their body into a shape resembling a peanut kernel, and hence their common name "peanut worm". They are usually deposit feeders. Peanut worms (made into a jelly) are considered a delicacy in some parts of China.

The above picture features an unidentified peanut worm found on a sandy shore.

E) Polychaetes (Class Polychaeta)

Polychaetes (class Polychaeta) are annelids found in the marine environment, and usually come with many (hence "poly") bristles ("chaeta").

Many polychaetes are free-living surface dwellers or active burrowers, and here are some of them:

Collarworms (family Eunicidae) usually has a collar of a different colour just behind the head, and hence the common name. Many species are omnivorous, and may feed on algae, small animals, and sometimes detritus or dead animals. Some are aggressive predators though, with sharp teeth that can cut small fishes or other small prey into two in one snap. Eunice grubei (inset) has candy cane markings on its antennae, blue eyes and an iridescent sheen. The larger photo shows a huge collarworm (Eunice sp.) that can also be found on our reefs. It is believed to be omnivorous, and is often seen snapping at nearby algae.

Fireworms (family Amphinomidae) are bristleworms with sharp, venom-filled bristles that break off upon contact, giving painful stings to the victim, and hence the common name. Most species can swim by flapping their parapodia (leg-like structures by the sides of their body) or moving their body side-to-side.

This fireworm, Eurythoe complanata, is commonly found under rocks. Many of these worms are able to reproduce asexually by breaking itself apart, and each fragment can grow into a viable individual worm.

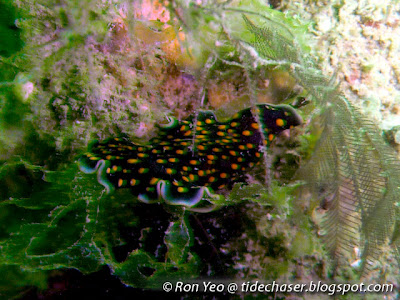

The Chloeia Fireworms (Chloeia spp.) are very colourful fireworms with fluffy, flap-like parapodia by their sides.

Ragworms (family Nereididae) are polychaetes which mostly has an eversible proboscis with a pair of claws at the tip. The predatory species used the proboscis to snap at their prey such as small crustaceans, while the herbivorous species used it to snap up algae. Some are found on rocky shores, while others burrow in mudflats or silty substrates. Unfortunately I do not have any photos of them yet.

Lugworms (family Arenicolidae) are large marine polychaetes that usually live in U-shaped burrows in sandy or muddy substrates. They swallow sand to digest the organic bits, then deposit the processed sand in coils at the exit of its burrow. These sand coils are known as casts, and is very similar to the casts deposited by acorn worms. It is often difficult to tell them apart just by looking at the casts without digging out the animal, and hence, the bigger photo above could be the cast of either one. Larger species, however, will leave a persistent small pile of sand (appearing like a miniature sand dune) as they continually deposit the sand from their back-ends, and as they swallow the sand, create round depressions when the surface sand collapse into the burrows at their front-ends. As such, if you see a small round depression with a small round mound nearby, there is a possibility that a lugworm may still be underneath.

Scale worms (families Polynoidae and Sigalionidae) are polychaete worms with plate-like scales on their back, believed to help them camouflage with the rocky habitat they live in. They mostly feed on small or sessile invertebrates. On a rocky shore, they normally forage during high tide, and hide in cracks or under rocks during low tide.

Blood worms (family Glyceridae) possess a long eversible proboscis, and are usually red in colour, hence the common name. They are usually found burrowing in mudflats or hiding under rocks and crevices in shallow waters, and may appear like earthworms due to the less conspicuous bristles when they are in the mud. They mostly feed on small invertebrates, though some also feed on detritus To hunt, the carnivorous species will track the prey in their burrow systems by sensing the changes in water pressure caused by its movements and shoot out their proboscis to grab it. The photo shows a Glycera rouxii.

Spaghetti Worms (family Terebellidae) have very long tentacles radiating from their front ends, resembling noodles, and hence the common name. They are deposit feeders - collecting detritus by spreading their long tentacles. A few other annelid families, such as Cirratulidae, Ampharetidae and Trichobranchidae, may also have species with similar long tentacles. Cirratulids will have tentacles occuring on most segments, not just the frontend, and they have a wedge-shaped head. Ampharetids have retractable tentacles (but not Terebellids). Trichobranchids are very similar but have long-handled hooks in the anterior region, and never in double rows. Unfortunately the photo above which I took was not clear enough to tell whether it's a terebellid or trichobranchid. It has tentacles with yellow and red bands.

Sometimes, several individuals can occur in the same tiny tidal pool. These unidentified worms have red tentacles.

While there are a lot of free-living polychaetes, many other polychaetes live in tube or tube-like structures, and generally these are called tube worms. The tubes are usually constructed with the mucus and sand, though some species also incorporate other available materials from their surroundings, such as leaves, twigs, shells and stones.

The chaetopeterids (family Chaetopteridae) built permanent fragile tubes and can be found in shallow waters on sandy or muddy shores, sometimes attached to hard surfaces. They usually occur in clusters, sometimes carpeting over wide areas. Many of these worms feed by flapping fan-like structures they possess to generate a water current, so as to trap plankton and other organic matter with the mucus nets they have constructed within their tube.

The onuphids (family Onuphidae) often incorporate materials from the surroundings, such as leaves and shells, to their tubes. Most species live in fixed tubes, but some are known to move around carrying their tubes, or even leave their tube to build new ones. They are commonly found on sandy or muddy shores in shallow waters. They are believed to be opportunistic omnivores, feeding on anything readily available, such as algae, decaying organic matter, small animals and even dead animals. They are characterised by tiny little bottle-brush-like structures on their sides, which appears like tiny fir trees when magnified. The above is likely to be the tube of a Diopatra sp.

The sabellariids (family Sabellariidae) build curved, tusk-shaped tubes, usually in colonies on rocks other other hard structures. They sometimes form extensive reefs, exhibiting a honeycomb-like appearance when viewed from the top, and hence they are also called honeycomb worms. They are suspension feeders, and use their tentacles to gather plankton to feed on. Unfortunately, I do not have good photos of them as yet.

The sabellids (family Sabellidae) have feather-like tentacles on their heads to filter plankton, hence giving them the common names "fan worm" or "featherduster worm". They are usually solitary and live in rough tubes. While most species live in fixed tubes, a few are known to be able to move around. When their body is exposed, the segments can be seen. Various species can be seen on our shores, and they come in different colours. The most commonly seen species is the Indian Fan Worm (Sabellastarte indica), as shown in the largest inset above with 2 individuals of different colour variations.

The serpulids (family Serpulidae) possess plume-like tentacular crowns, and hence are also called "plume worms". They live in calcareous tubes and filter plankton from the water to feed on with their tentacles. Examples include the keel worms (see above photo), which are commonly found cemented to rocks and other hard surfaces. The "keel" refers to the shape of the tube, which somewhat resembles the keel of a boat.

References

Generally, the segmented annelids will have a body comprising identical segments (excluding the head and tail) containing the same set of organs, and in some cases, external structures used for locomotion. They should not be confused with arthropods like millipedes and centipedes, which will have segment legs that annelids lack. The above picture features an unidentified annelid worm.

The unsegmented annelids are believed to have lost the segments through evolution to better adapt to survive in their habitats.

Many annelids, except leeches, are known to be able to regenerate lost body parts, even their heads. A number of species can also reproduce asexually by splitting into two or several parts and regrow the lost parts. Some annelids can even regrow from severe damages, such as from a single segment! Most also reproduce sexually, and are mostly hermaphrodites with both male and female reproductive organs.

A) Earthworms (Class Oligochaeta)

Earthworms (subclass Oligochaeta) are possible the group of annelids that most Singaporeans are familiar with. The name "Oligochaeta" is means "a few (oligo) bristles (chaeta)", and the oligochaetes previously include the leeches, but studies have shown that the leeches should be placed on a separate class of their own. Earthworms are burrowing annelids which play important ecological roles in many terrestrial ecosystems. They aerate the soil as they burrow, and bring nutrients from underground to the surface. They also break down organic matter into humus to improve soil fertility, and is the prey of many animals, making them an important part of the food web. Their ability to regenerate lost body parts varies between species - some can grow into two new worms after they are bisected, while for others only one half will survive.

The above picture features an unidentified earthworm. Earthworms are generally hard to identified in the field, as specimens usually need to be examined under the microscope to check for the arrangement of the tiny hair-like structures to determine the species.

B) Leeches (Class Clitellata: Subclass Hirudinea)

Many people are familiar with leeches (class Clitellata: subclass Hirudinea) for their blood diet, but actually, most species feed on small invertebrates, and only some feed on blood. Depending on the species and habitat, the hosts of the blood-sucking species may be mammals, fishes, birds, reptiles or even snails. They detect their hosts by their odour, body heat or vibrations from their movements, and attach themselves to the latter with their sharp jaws in their mouth and strong suckers at the rear. They secrete an enzyme to prevent the blood from clotting, and drop off when they are full of blood.

The above photo features a Buffalo Leech (Hirudinaria sp.), which is sometimes encountered in freshwater habitats such as streams and ponds. Some marine leech species can also be found in Singapore, but the terrestrial species may have disappeared already due to the low mammal population in our forest.

C) Spoon Worms (Class Echiura)

The annelids include a few unsegmented worms, and the spoon worm (class Echiura) is one of them. Spoon worms are previously regarded as a phylum of their own, but recent phylogenetic studies showed that they are annelids. They are usually found in muddy or sandy substrates, though some species live under rocks too. They have a flattened proboscis (the whitish structure in the photo) which resembles a spoon on their front ends. They are usually filter feeders, and raising the proboscis out of their burrows to collect plankton and tiny organic matter.

The above picture features an unidentified spoon worm, which was found on a sandy-muddy shore.

D) Peanut Worms (Class Sipuncula)

Peanut worms (class Sipuncula) are previously regarded as a phylum of their own as well, but again, recent studies showed that they are also annelids. The body of a peanut worm comprises an unsegmented trunk and a retractable structure called an "introvert". When disturbed, they can retract their body into a shape resembling a peanut kernel, and hence their common name "peanut worm". They are usually deposit feeders. Peanut worms (made into a jelly) are considered a delicacy in some parts of China.

The above picture features an unidentified peanut worm found on a sandy shore.

E) Polychaetes (Class Polychaeta)

Polychaetes (class Polychaeta) are annelids found in the marine environment, and usually come with many (hence "poly") bristles ("chaeta").

Many polychaetes are free-living surface dwellers or active burrowers, and here are some of them:

Collarworms (family Eunicidae) usually has a collar of a different colour just behind the head, and hence the common name. Many species are omnivorous, and may feed on algae, small animals, and sometimes detritus or dead animals. Some are aggressive predators though, with sharp teeth that can cut small fishes or other small prey into two in one snap. Eunice grubei (inset) has candy cane markings on its antennae, blue eyes and an iridescent sheen. The larger photo shows a huge collarworm (Eunice sp.) that can also be found on our reefs. It is believed to be omnivorous, and is often seen snapping at nearby algae.

Fireworms (family Amphinomidae) are bristleworms with sharp, venom-filled bristles that break off upon contact, giving painful stings to the victim, and hence the common name. Most species can swim by flapping their parapodia (leg-like structures by the sides of their body) or moving their body side-to-side.

This fireworm, Eurythoe complanata, is commonly found under rocks. Many of these worms are able to reproduce asexually by breaking itself apart, and each fragment can grow into a viable individual worm.

The Chloeia Fireworms (Chloeia spp.) are very colourful fireworms with fluffy, flap-like parapodia by their sides.

Ragworms (family Nereididae) are polychaetes which mostly has an eversible proboscis with a pair of claws at the tip. The predatory species used the proboscis to snap at their prey such as small crustaceans, while the herbivorous species used it to snap up algae. Some are found on rocky shores, while others burrow in mudflats or silty substrates. Unfortunately I do not have any photos of them yet.

Lugworms (family Arenicolidae) are large marine polychaetes that usually live in U-shaped burrows in sandy or muddy substrates. They swallow sand to digest the organic bits, then deposit the processed sand in coils at the exit of its burrow. These sand coils are known as casts, and is very similar to the casts deposited by acorn worms. It is often difficult to tell them apart just by looking at the casts without digging out the animal, and hence, the bigger photo above could be the cast of either one. Larger species, however, will leave a persistent small pile of sand (appearing like a miniature sand dune) as they continually deposit the sand from their back-ends, and as they swallow the sand, create round depressions when the surface sand collapse into the burrows at their front-ends. As such, if you see a small round depression with a small round mound nearby, there is a possibility that a lugworm may still be underneath.

Scale worms (families Polynoidae and Sigalionidae) are polychaete worms with plate-like scales on their back, believed to help them camouflage with the rocky habitat they live in. They mostly feed on small or sessile invertebrates. On a rocky shore, they normally forage during high tide, and hide in cracks or under rocks during low tide.

Blood worms (family Glyceridae) possess a long eversible proboscis, and are usually red in colour, hence the common name. They are usually found burrowing in mudflats or hiding under rocks and crevices in shallow waters, and may appear like earthworms due to the less conspicuous bristles when they are in the mud. They mostly feed on small invertebrates, though some also feed on detritus To hunt, the carnivorous species will track the prey in their burrow systems by sensing the changes in water pressure caused by its movements and shoot out their proboscis to grab it. The photo shows a Glycera rouxii.

Spaghetti Worms (family Terebellidae) have very long tentacles radiating from their front ends, resembling noodles, and hence the common name. They are deposit feeders - collecting detritus by spreading their long tentacles. A few other annelid families, such as Cirratulidae, Ampharetidae and Trichobranchidae, may also have species with similar long tentacles. Cirratulids will have tentacles occuring on most segments, not just the frontend, and they have a wedge-shaped head. Ampharetids have retractable tentacles (but not Terebellids). Trichobranchids are very similar but have long-handled hooks in the anterior region, and never in double rows. Unfortunately the photo above which I took was not clear enough to tell whether it's a terebellid or trichobranchid. It has tentacles with yellow and red bands.

Sometimes, several individuals can occur in the same tiny tidal pool. These unidentified worms have red tentacles.

While there are a lot of free-living polychaetes, many other polychaetes live in tube or tube-like structures, and generally these are called tube worms. The tubes are usually constructed with the mucus and sand, though some species also incorporate other available materials from their surroundings, such as leaves, twigs, shells and stones.

The chaetopeterids (family Chaetopteridae) built permanent fragile tubes and can be found in shallow waters on sandy or muddy shores, sometimes attached to hard surfaces. They usually occur in clusters, sometimes carpeting over wide areas. Many of these worms feed by flapping fan-like structures they possess to generate a water current, so as to trap plankton and other organic matter with the mucus nets they have constructed within their tube.

The onuphids (family Onuphidae) often incorporate materials from the surroundings, such as leaves and shells, to their tubes. Most species live in fixed tubes, but some are known to move around carrying their tubes, or even leave their tube to build new ones. They are commonly found on sandy or muddy shores in shallow waters. They are believed to be opportunistic omnivores, feeding on anything readily available, such as algae, decaying organic matter, small animals and even dead animals. They are characterised by tiny little bottle-brush-like structures on their sides, which appears like tiny fir trees when magnified. The above is likely to be the tube of a Diopatra sp.

The sabellariids (family Sabellariidae) build curved, tusk-shaped tubes, usually in colonies on rocks other other hard structures. They sometimes form extensive reefs, exhibiting a honeycomb-like appearance when viewed from the top, and hence they are also called honeycomb worms. They are suspension feeders, and use their tentacles to gather plankton to feed on. Unfortunately, I do not have good photos of them as yet.

The sabellids (family Sabellidae) have feather-like tentacles on their heads to filter plankton, hence giving them the common names "fan worm" or "featherduster worm". They are usually solitary and live in rough tubes. While most species live in fixed tubes, a few are known to be able to move around. When their body is exposed, the segments can be seen. Various species can be seen on our shores, and they come in different colours. The most commonly seen species is the Indian Fan Worm (Sabellastarte indica), as shown in the largest inset above with 2 individuals of different colour variations.

The serpulids (family Serpulidae) possess plume-like tentacular crowns, and hence are also called "plume worms". They live in calcareous tubes and filter plankton from the water to feed on with their tentacles. Examples include the keel worms (see above photo), which are commonly found cemented to rocks and other hard surfaces. The "keel" refers to the shape of the tube, which somewhat resembles the keel of a boat.

References

- Chan, W.M.F. 2009. New nereidid records (Annelida, Polychaeta) from mangroves and sediment flats of Singapore. Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, Supplement No. 22: 159-172

- Glasby, C.J., 1999. The Namanereidinae (Polychaeta: Nereididae). Part 1, Taxonomy and Phylogeny. Records of the Australian Museum, Supplement 25: 1-129.

- Ruppert, E.E. and R.D. Barnes. 1991. Invertebrate Zoology (International Edition). Saunders College Publishing. U.S.A. 1056 pp.

- Tan, L.T. & L.M. Chou, 1993. Checklist of polychaete species from Singapore waters (Annelida). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology, 41(2): 279-295.

- Wilson, R.S., P.A. Hutchings & C.J.Glasby (eds), 2003. Polychaetes: An Interactive Identification Guide. CISRO Publishing, Melbourne.

- Fauchald, K., & P. A. Jumars. 1979. The diet of worms: a study of polychaete feeding guilds. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 17: 193-284.