The Pasir Ris Mangrove Boardwalk is located in a 6-hectare mangrove forest in Pasir Ris Park, a park managed by the National Parks Board (NParks) in the northeastern part of Singapore. In Malay, "Pasir" means "beach", while "Ris" means "bolt-rope", refering to the narrow beach.

Do take a look at the map provided at the NParks Website to find out how you can get to the boardwalk, and also where are the various entrances.

Dos & Don'ts

What to Expect at the Boardwalk

The mangrove forest at Pasir Ris is surprisingly diverse despite its small size, and a good number of nationally endangered or critically endangered plant species can be found here. On top of that, NParks has also done a good job of replanting more mangrove plants to increase the gene pool. Unfortunately, the area no longer receives the much needed mud from the rivers as they have been canalised, and hence the substrate is slowly firming up as the incoming tides deposit more and more sand. As a result, NParks had to resort to digging trenches into the back mangroves so that the plants will get the sea water. In the meantime, the front mangroves are slowly being eroded by the waves and receding tides, and several coastal protection measures such as reforestation and beach nourishment (using sand bags) are implemented. The Pasir Ris Mangrove hence does not only provide outdoor learning opportunities on mangrove ecology, biodiversity and conservation, but coastal protection as well.

At the Back Mangrove

The boardwalk at Pasir Ris Mangroves makes a good loop around the true mangrove and back mangrove zones. As the name implies, the back mangrove occurs at the back of the mangrove forest further away from salt water sources, which can be the sea or tidal rivers. The back mangrove is seldom inundated with sea water, and hence the species found here (i.e. the coastal plants) are not as tolerant of soaking their roots in salt water compared to the true mangrove species. However, the coastal plants here will still have to tolerate salt sprays brought by the waves and wind. As a result, many coastal plants have smooth leaves to allow the salt formed on them to be easily swept away by the wind and rain.

Coastal plants also have to adapt to the dry conditions in the windy coastal environment, being caught in the middle of land and sea breezes which increase the rate of evaporation. The dry conditions are especially acute at sandy areas which could not trap much water due to the porous nature of the substrate. Hence, many coastal plants go either extremes of having thick leathery leaves to retain water, or thin and narrow leaves to reduce the rate of evaporation.

Those growing on more exposed areas will have to tolerate the heat and radiation from the sun, and thus the leaves of many coastal plants come with a glossy surface to help reflect the heat and radiation.

Some of the back mangrove plants occuring naturally (not planted) and animals found along the Pasir Ris Mangrove Boardwalk are highlighted here:

Once you get under the vegetation, you will probably hear the distinctive and continuous cicada song made by the cicadas (Family Cicadidae). The males "sing" by vibrating special structures called "timbals" on the sides of the male cicada's abdomen, in order to attract female cicadas. In addition to the mating song, some cicadas are known to be able to produce distress call (when they are caught) or courtship songs.

In the secondary forest and edge of the back mangrove here, the Fishtail Palm (Caryota mitis) can be commonly seen. Interestingly, the plant starts bearing flowers from the top of the trunk, and subsequent bunches will appear below the previous bunch near the base of a leaf stalk. The leaves and fruits contain oxalate crystals and are toxic, and may cause burns on the skin when touched.

Nonetheless, some animals such as civets and hornbills are known to consume the fruits and help disperse the seeds, and the Oriental Pied-hornbills (Anthracoceros albirostris) is one of them. They are sometimes seen feeding on the fruits of the various species of palms here. Believed to have gone extinct in the early 1900s in Singapore, the current population is thought to be the descendants of those which have flown over from Johor to settle down on Pulau Ubin in the 1990s. Breeding was first recorded in 1997 on Pulau Ubin, and since then, several of them have flown over to settle down in Changi. Several pairs have also been released at various parks by NParks.

At the landward side of the back mangrove, the Sea Apple (Syzygium grande) also occurs naturally. It is commonly planted as a roadside tree for its shade, and previously it is also planted as fire breaks as it is quite fire-resistant (being a coastal plant, it has adapted to survive in the dry environment by retaining water in its trunk and leathery leaves). The wood is used for building boat and houses.

The Pong Pong (Cerbera odollam) occurs more on the landward side of the back mangrove as well. has pretty white flowers with a yellow centre, while the fruit is round, turning red to dark purple with age. The fruits are dispersed by water. The seed, sap and leaf are very poisonous. It is sometimes planted as a wayside tree, and the dried fibre mesh of the fruit is sometimes used in flower arrangement.

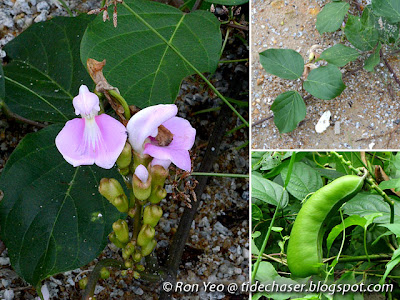

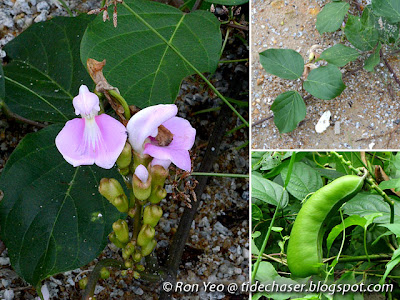

The Maunaloa (Canavalia cathartica), a common seashore creeper/climber, is also found here. Studies shown the beans to be highly nutritional, and scientists are exploring the possibility of exploiting it as a solution for food scarcity in developing countries. However, it is mildly toxic, and hence for it to be safely consumed, they are usually soaked overnight to support microbial fermentation to break down the toxins, and then boiled or roasted.

The Senduduk (Melastoma malabathricum) is a very common shrub in our forests and open areas, and they can be found on the landward side of the back mangrove too. The ripe fruits can be eaten but stain the mouth black, hence the genus name Melastoma, which means "black mouth". The young leaves are edible as well, and are used to treat stomach complains.

The Sea Daisy (Melanthera biflora) is a straggling to climbing herb with lovely yellow composite flowers, and usually occurs on sandy beaches, mangrove edge and sometimes inland open area. The leaves have lots of medicinal properties, and are used to treat cuts, stings and ulcer. It can be consumed to treat stomach pains and to improve healing after childbirth.

It is around here at the edge of the back mangrove on the landward side, families of Red Jungle Fowls (Gallus gallus) can be regularly seen. This species of wild chicken is believed to be the ancestor of the domestic chicken. The former, however, can be differentiated from the latter by the white cheek, white rump, grey legs, and the calls of the male which have an abrupt ending. They are usually found in wooded areas, forest edges and open areas near forests.

The Sea Almond (Terminalia catappa) is commonly found along beaches and at the back mangrove. It is deciduous, shedding its leaves twice a year, and the leaves turn orange or red before they are shed. The branching is somewhat layered horizontally, and hence they are also called pagoda tree. The kernel of the fruit is edible, and taste somewhat like almond, hence the common name.

Plantain Squirrels (Callosciurus notatus) can be seen feeding on the Sea Almond or Sea Apple fruits sometimes, or jumping from branch to branch, or even tree to tree! They eat mainly fruit and nuts, but are also known to feed on small insects.

The Kacang Kayu Laut (Pongamia pinnata) is a common seashore tree with pretty pinkish-white to purplish flowers and thick leathery seed pods. The oil from the seeds are used for illumination and for medicinal purposes. Recently, there were suggestions to use the oil as biofuel as well. The seeds and roots are used to make fish poison.

Sometimes, you can find Bird's-nest Ferns (Asplenium nidus) growing on some of the trees, which got its common name from its resemblance to bird's nest (with some imagination). The rosette of leaves traps dead leaves, resulting in a spongy humus that traps rain water, useful for the plant especially in the dry coastal environment.

Occuring nearer to the true mangrove area, the Sea Hibiscus (Talipariti tiliaceum), with its pretty heart-shaped leaves, is also commonly seen in Singapore. Interestingly, the flowers are yellow in the morning, but turn orange or red towards the end of the day, and will be shed usually by the next day. The fibre from the bark is used to make ropes and caulk boats.

And when there are Sea Hibiscus trees, you will often find Cotton Stainer Bugs (Dysdercus decussatus) which feed on the seeds. They got their common name from a related species which feeds on cotton seeds, and introduce a fungus which stains the cotton.

Appearing rather similar to the Sea Hibiscus, the Portia Tree (Thespesia populnea) has narrowly heart-shaped leaves.

And the Portia Tree is also the host for a closely related but much rarer cotton stainer species, the Thespesia Firebug (Dysdercus simon). They can be differentiated from the Sea Hibiscus' Cotton Stainer Bug by the black head.

Various species of Sea Holly (Acanthus spp.) can also be seen here. They got their common name from their resemblance with the Christmas holly. These plants can be found growing in saline conditions, and they are able to excrete the excess salt through glands on the top surface of their leaves.

The Mangrove Derris (Derris trifoliata) is a very common woody climber in the mangroves. This plant is poisonous, and pounded leaves and roots are used to stun fish, and also as an insecticide. The poison will be broken down after cooking. This fishing method, however, is not encouraged as it harms not just the fish the fishermen want, but other animals in the area as well.

Pasir Ris houses a few critically endangered mangrove climbers, and the Sea Rubber Vine (Gymnanthera oblonga) is one of them. The fruits of this plant usually occur in pairs, and are eaten in Papua New Guinea.

The Kalak Kambing (Finlaysonia obovata) is another critically endangered climber found here. The fruits appear like a pair of horns, and hence the common name "kalak kambing", which means goat's horn. The young leaves are apparently eaten by some as a vegetable.

At the Front Mangrove

True mangrove species refer to those that grow only in mangrove environment. They are adapted to survive in waterlogged and anaerobic conditions. The substrate they are growing on are usually muddy and unstable as well. That is why many of the trees have roots exposed to the air to take in more oxygen, and the roots often spread over a wide area to allow the trees to stabilise themselves on the soft mud. The roots also have to be adapted to survive in the saline conditions. Here are some of the animals and true mangrove species found at the front mangrove area:

The Nyireh Batu (Xylocarpus moluccensis), a rarer relative of the more commonly seen Nyireh Bunga (Xylocarpus granatum) which is also found here, is doing surprisingly well along the boardwalk. The various Xylocarpus species are usually called Mangrove Cannonball for their round fruits, which break upon drying or when they hit the ground, and the seeds are dispersed by water.

The Atlas Moth (Attacus atlas) appear to like feeding on the leaves of the Niyreh Batu (and various other true and back mangrove plant species). This moth is the biggest moth in the world in terms of total wing surface area, and its wingspan is also one of the widest, up to 30cm.

The Buta-buta (Excoecaria agallocha) usually occurs towards the landward side of the true mangrove habitat. It is also called "Blind-your-eyes", has poisonous white sap which can cause blistering and blindness. The tree is also deciduous, and the leaves turn yellow, orange or even reddish before they are shed.

The blind-your-eyes tree can often be found growing on mud lobster mounds, which appears like little volcanoes among the mud. Mud Lobsters (Thalassina sp.) eat tiny organic particles in the mud, and as they process the huge amounts of mud and sand to seek food, the processed mud is piled around their burrows, forming the little "volcano-like" structures. Mud lobsters play an important role of bringing nutrient-rich soil to the surface. Many other plants and animals live in or on mud lobster mounds too, attracted by the nutrients, and also, higher ground and free lodging (burrow made by the mud lobster) to get away from the sea water.

The Teruntum Merah (Lumnitzera littorea) also occurs here. It has pretty red flowers, and even the young branches are reddish in colour. The wood is hard and extremely durable, and is used for the building of bridges, wharves, cart axles, flooring and sleepers. It has a rose-like scent, making it popular as a cabinet timber.

An animal commonly seen on mud lobster mounds is the Tree-climbing Crab (Episesarma sp.), which usually dig burrows into the mounds or at the base of trees. During high tide, you may encounter many of them climbing up to trees to avoid the predatory fishes in the water. Tree-climbing crabs are primarily leaf-eaters. They are also called vinegar crabs, because the Teochews are known to pickle this crab in black sauce with vinegar.

The Mangrove Pitta (Pitta megarhyncha) can occasionally be seen foraging among the mud lobster mounds, in both the true and back mangrove habitats. It has been observed to feed on slugs, snails and small crabs. It is a rare resident in Singapore, and globally near-threatened due to loss of habitat.

Moving seaward, the Nipah Palm (Nypa fruticans) is the only true mangrove palm in Singapore. Also called the Attap Palm, its seed (called "attap chee") is edible is added to several local desserts, such as the ice kacang. The leaves are used for thatching. A sweet syrup can be extracted from the flower stalk in large quantities and made into palm sugar, or used in the production of alcohol (including ‘toddy’), sugar and vinegar.

The Bakau Minyak (Rhizophora apiculata), like other Rhizophora species, has prop roots and stilt roots at the lower part of the tree. The wood is hard and heavy, and is used for making scaffolding and furniture. It is widely used for making charcoal. This tree is often planted along fish ponds to protect the bunds. It can occur quite close to the sea.

Among the roots and in the mud, the Orange Mud Crab (Scylla olivacea), which is the mud crab often used in the popular "Chilli Crab" dish. These crabs usually feed on clams which they crush with their powerful claws. They are very valuable in the local market, and are used in various popular local dishes.

The Lenggadai (Bruguiera parviflora) is rather uncommon in other mangroves, but there is a good population at Pasir Ris along the boardwalk. The wood from this tree produces good charcoal and pulp. It is usually used as firewood or for mining and making fishing-stakes. The germinating seedling is sometimes eaten as a vegetable.

Another common mangrove tree here nearer to the seaward side is the Perepat (Sonneratia alba). Like other Sonneratia species, it has conical roots protruding from the ground. The fruits and leaves are edible, while the wood is used for various construction purposes, such as the construction of buildings, bridges, boats, wooden tools and furniture.

There is a nesting colony of Grey Herons (Ardea cinerea) on some of the Perepat trees along Sungei Tampines. One of the biggest bird in Singapore, it can reach heights of about 1m, and has a light grey plumage. The long legs enable it to wade in shallow water or among tall grasses to hunt small animals, such as fishes, amphibians, reptiles, insects, crustaceans and even small mammals and birds.

The Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) is often seen here too. This is a nocturnal bird, and usually roost in trees in the day. It has gotten its common name from its black crown. This heron lacks the long neck of the previous species (though the neck can stretch quite far out), but is still fairly tall (about 65cm). Like the other herons, it feeds on small animals.

Another rather common mangrove tree here is the Ceriops zippeliana, which was only discovered to be a new species in recent studies. The Ceriops, Rhizophora and Bruguiera mangrove trees demonstrate vivipary, a condition whereby the young plant within the seed grows first to break through the seed coat then out of the fruit wall while still attached to the parent plant. Since the mangrove habitat is a very harsh environment, these plants have adapted such that the parent plants prepare their young as much as possible to increase their chances of survival. The seedlings are dispersed by water. They float horizontally for a few weeks, during which the root (lower part) will absorb water and become heavier, eventually causing the seedlings to tip and float vertically. As the tide goes down, the vertically-oriented seedling will sink into the mud or other suitable substrates. Most of the seedlings, however, end up being washed ashore or eaten by animals.

The Rhizophora, Bruguiera and Ceriops, together with the Perepet also deal with the saline conditions in a similar manner. They can selectively absorb only certain ions from the sea water through a process called ultrafiltration. But this process is not 100% effective, and some salt still gets into the trees, and will be removed by transpiration of the leaf surfaces or accumulated in old leaves.

The Api-api Putih (Avicennia alba) and other Avicennia species, on the other hand, not only exclude salt from entering the plant, but has salt glands on the leaves to excrete part of the remaining quantity of salt. "Api-api" means "fire-fire" or "firefly" in Malay, as some Avicennia species are noted to attract fireflies.

On the trunks of these mangrove trees, various snails, such as the conical Chut-chut (Cerithidea spp.) and the round Articulate Nerites (Nerita articulata) above. The Chut-chut got its name from the way the cooked snails are eaten - by sucking the content out from the shell, making a "chut-chut" sound. The Articulate Nerites got their names from their shells' appearance - the shell looks as if it consists of sections united by joints (meaning of articulate in anatomy). Both feed on algae.

Many fishes occurs in the mangroves, and the Giant Mudskipper (Periophthalmodon schlosseri) is one of them. This is the largest mudskipper species in Singapore. It is able to survive out of water by holding water in its mouth and gill chambers. It can breathe through its skin when it is wet too. Being a rather aggressive fish, it feeds on other small animals, such as crabs or worms.

The Spotted Archerfish (Toxotes chatareus) is yet another fish that can be seen here. This fish feeds on insects by shooting them down with water. They may also jump out of the water to get their prey if they are near enough.

And if there are fishes, there will be kingfishers! The Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris) is one of the commonest kingfisher in Singapore. Most of the time, they could be well-hidden among the foliage, but you could often still hear the distinctive cackling call. They do not just feed on fish though, but insects as well.

Towards the end and beginning of the year, migratory waders can also be seen here. The photo above shows two Whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus). They feed on worms in the mud by digging them out with their long beaks.

Pasir Ris Mangrove is perhaps also one of the most convenient place on mainland Singapore to see the Dog-faced Water Snake (Cerberus rynchops). This snake is mildly venomous and feed on small fishes. It sometimes hunt other small animals too. It is usually easier to see them at night, in the early morning or late afternoon when it is cooler and darker.

Conserving Pasir Ris Mangrove Forest

The entire Pasir Ris Park is currently managed by NParks, but it is still very vulnerable to possible development plans in future. There are also problems of poachers who collect plants and animals without an NParks permit, and anglers not disposing disused fishing lines properly. The latter is especially an issue and many animals got entangled in the lines and either starve to death or get badly wounded. There is also the rubbish issue, as the park users may not have disposed their waste properly and animals may end up eating or getting trapped in them.

As such, it is important that Singaporeans visiting this park should behave in a more responsible manner. It is important for Singaporeans to learn more about our various nature spots, the issues they face, so that we can better protect what is left. Hence, I always encourage those who visit my blog to read up more about our natural heritage from books or online resources.

It is also important that nature lovers do share your experience with their friends so that more people get to know and visit Chek Jawa. And if time permits, become a volunteer to help with conducting guided walks here!

At the end of the day, we also hope that more Singaporeans can feedback to the government if they enjoy visiting our nature spots and hope to preserve them as they are, so that the authorities will know that we do value our natural heritage and these nature spots will be protected.

Do take a look at the map provided at the NParks Website to find out how you can get to the boardwalk, and also where are the various entrances.

Dos & Don'ts

- Stay on the trail! Wandering off the trail may result in trampling of the flora and fauna.

- Bring water and some light snacks, but avoid eating or drinking when there are monkeys around.

- Do not feed any animals, as they may become very dependent on human to feed them, and forget how to find food on their own. Some animals, such as the macaques, may even learn to snatch food from human.

- Keep your volume down, or you may disturb the very animals you want to see, and they may hide away from you.

- Take nothing but photos, leave nothing but foot prints. Bring your litter out with you, and never take anything from the forest. Poaching has resulted in severe reduction in the population of much wildlife in many places.

- You may want to consider wearing long pants, e.g. light track pants etc. There could be mosquitoes.

- Please bring insect repellent. Mosquito pads are usually not very useful for such outdoor activities as the mosquitoes can be quite aggressive.

- Please bring a cap/hat in case of sunny weather, and raincoat/poncho in case of wet weather. I would also recommend bringing a few plastic bags to keep your electronic products in case it rains.

- Bring a camera along, but remember to have a plastic bag to keep it dry in case it rains.

What to Expect at the Boardwalk

The mangrove forest at Pasir Ris is surprisingly diverse despite its small size, and a good number of nationally endangered or critically endangered plant species can be found here. On top of that, NParks has also done a good job of replanting more mangrove plants to increase the gene pool. Unfortunately, the area no longer receives the much needed mud from the rivers as they have been canalised, and hence the substrate is slowly firming up as the incoming tides deposit more and more sand. As a result, NParks had to resort to digging trenches into the back mangroves so that the plants will get the sea water. In the meantime, the front mangroves are slowly being eroded by the waves and receding tides, and several coastal protection measures such as reforestation and beach nourishment (using sand bags) are implemented. The Pasir Ris Mangrove hence does not only provide outdoor learning opportunities on mangrove ecology, biodiversity and conservation, but coastal protection as well.

At the Back Mangrove

The boardwalk at Pasir Ris Mangroves makes a good loop around the true mangrove and back mangrove zones. As the name implies, the back mangrove occurs at the back of the mangrove forest further away from salt water sources, which can be the sea or tidal rivers. The back mangrove is seldom inundated with sea water, and hence the species found here (i.e. the coastal plants) are not as tolerant of soaking their roots in salt water compared to the true mangrove species. However, the coastal plants here will still have to tolerate salt sprays brought by the waves and wind. As a result, many coastal plants have smooth leaves to allow the salt formed on them to be easily swept away by the wind and rain.

Coastal plants also have to adapt to the dry conditions in the windy coastal environment, being caught in the middle of land and sea breezes which increase the rate of evaporation. The dry conditions are especially acute at sandy areas which could not trap much water due to the porous nature of the substrate. Hence, many coastal plants go either extremes of having thick leathery leaves to retain water, or thin and narrow leaves to reduce the rate of evaporation.

Those growing on more exposed areas will have to tolerate the heat and radiation from the sun, and thus the leaves of many coastal plants come with a glossy surface to help reflect the heat and radiation.

Some of the back mangrove plants occuring naturally (not planted) and animals found along the Pasir Ris Mangrove Boardwalk are highlighted here:

Once you get under the vegetation, you will probably hear the distinctive and continuous cicada song made by the cicadas (Family Cicadidae). The males "sing" by vibrating special structures called "timbals" on the sides of the male cicada's abdomen, in order to attract female cicadas. In addition to the mating song, some cicadas are known to be able to produce distress call (when they are caught) or courtship songs.

In the secondary forest and edge of the back mangrove here, the Fishtail Palm (Caryota mitis) can be commonly seen. Interestingly, the plant starts bearing flowers from the top of the trunk, and subsequent bunches will appear below the previous bunch near the base of a leaf stalk. The leaves and fruits contain oxalate crystals and are toxic, and may cause burns on the skin when touched.

Nonetheless, some animals such as civets and hornbills are known to consume the fruits and help disperse the seeds, and the Oriental Pied-hornbills (Anthracoceros albirostris) is one of them. They are sometimes seen feeding on the fruits of the various species of palms here. Believed to have gone extinct in the early 1900s in Singapore, the current population is thought to be the descendants of those which have flown over from Johor to settle down on Pulau Ubin in the 1990s. Breeding was first recorded in 1997 on Pulau Ubin, and since then, several of them have flown over to settle down in Changi. Several pairs have also been released at various parks by NParks.

At the landward side of the back mangrove, the Sea Apple (Syzygium grande) also occurs naturally. It is commonly planted as a roadside tree for its shade, and previously it is also planted as fire breaks as it is quite fire-resistant (being a coastal plant, it has adapted to survive in the dry environment by retaining water in its trunk and leathery leaves). The wood is used for building boat and houses.

The Pong Pong (Cerbera odollam) occurs more on the landward side of the back mangrove as well. has pretty white flowers with a yellow centre, while the fruit is round, turning red to dark purple with age. The fruits are dispersed by water. The seed, sap and leaf are very poisonous. It is sometimes planted as a wayside tree, and the dried fibre mesh of the fruit is sometimes used in flower arrangement.

The Maunaloa (Canavalia cathartica), a common seashore creeper/climber, is also found here. Studies shown the beans to be highly nutritional, and scientists are exploring the possibility of exploiting it as a solution for food scarcity in developing countries. However, it is mildly toxic, and hence for it to be safely consumed, they are usually soaked overnight to support microbial fermentation to break down the toxins, and then boiled or roasted.

The Senduduk (Melastoma malabathricum) is a very common shrub in our forests and open areas, and they can be found on the landward side of the back mangrove too. The ripe fruits can be eaten but stain the mouth black, hence the genus name Melastoma, which means "black mouth". The young leaves are edible as well, and are used to treat stomach complains.

The Sea Daisy (Melanthera biflora) is a straggling to climbing herb with lovely yellow composite flowers, and usually occurs on sandy beaches, mangrove edge and sometimes inland open area. The leaves have lots of medicinal properties, and are used to treat cuts, stings and ulcer. It can be consumed to treat stomach pains and to improve healing after childbirth.

It is around here at the edge of the back mangrove on the landward side, families of Red Jungle Fowls (Gallus gallus) can be regularly seen. This species of wild chicken is believed to be the ancestor of the domestic chicken. The former, however, can be differentiated from the latter by the white cheek, white rump, grey legs, and the calls of the male which have an abrupt ending. They are usually found in wooded areas, forest edges and open areas near forests.

The Sea Almond (Terminalia catappa) is commonly found along beaches and at the back mangrove. It is deciduous, shedding its leaves twice a year, and the leaves turn orange or red before they are shed. The branching is somewhat layered horizontally, and hence they are also called pagoda tree. The kernel of the fruit is edible, and taste somewhat like almond, hence the common name.

Plantain Squirrels (Callosciurus notatus) can be seen feeding on the Sea Almond or Sea Apple fruits sometimes, or jumping from branch to branch, or even tree to tree! They eat mainly fruit and nuts, but are also known to feed on small insects.

The Kacang Kayu Laut (Pongamia pinnata) is a common seashore tree with pretty pinkish-white to purplish flowers and thick leathery seed pods. The oil from the seeds are used for illumination and for medicinal purposes. Recently, there were suggestions to use the oil as biofuel as well. The seeds and roots are used to make fish poison.

Sometimes, you can find Bird's-nest Ferns (Asplenium nidus) growing on some of the trees, which got its common name from its resemblance to bird's nest (with some imagination). The rosette of leaves traps dead leaves, resulting in a spongy humus that traps rain water, useful for the plant especially in the dry coastal environment.

Occuring nearer to the true mangrove area, the Sea Hibiscus (Talipariti tiliaceum), with its pretty heart-shaped leaves, is also commonly seen in Singapore. Interestingly, the flowers are yellow in the morning, but turn orange or red towards the end of the day, and will be shed usually by the next day. The fibre from the bark is used to make ropes and caulk boats.

And when there are Sea Hibiscus trees, you will often find Cotton Stainer Bugs (Dysdercus decussatus) which feed on the seeds. They got their common name from a related species which feeds on cotton seeds, and introduce a fungus which stains the cotton.

Appearing rather similar to the Sea Hibiscus, the Portia Tree (Thespesia populnea) has narrowly heart-shaped leaves.

And the Portia Tree is also the host for a closely related but much rarer cotton stainer species, the Thespesia Firebug (Dysdercus simon). They can be differentiated from the Sea Hibiscus' Cotton Stainer Bug by the black head.

Various species of Sea Holly (Acanthus spp.) can also be seen here. They got their common name from their resemblance with the Christmas holly. These plants can be found growing in saline conditions, and they are able to excrete the excess salt through glands on the top surface of their leaves.

The Mangrove Derris (Derris trifoliata) is a very common woody climber in the mangroves. This plant is poisonous, and pounded leaves and roots are used to stun fish, and also as an insecticide. The poison will be broken down after cooking. This fishing method, however, is not encouraged as it harms not just the fish the fishermen want, but other animals in the area as well.

Pasir Ris houses a few critically endangered mangrove climbers, and the Sea Rubber Vine (Gymnanthera oblonga) is one of them. The fruits of this plant usually occur in pairs, and are eaten in Papua New Guinea.

The Kalak Kambing (Finlaysonia obovata) is another critically endangered climber found here. The fruits appear like a pair of horns, and hence the common name "kalak kambing", which means goat's horn. The young leaves are apparently eaten by some as a vegetable.

At the Front Mangrove

True mangrove species refer to those that grow only in mangrove environment. They are adapted to survive in waterlogged and anaerobic conditions. The substrate they are growing on are usually muddy and unstable as well. That is why many of the trees have roots exposed to the air to take in more oxygen, and the roots often spread over a wide area to allow the trees to stabilise themselves on the soft mud. The roots also have to be adapted to survive in the saline conditions. Here are some of the animals and true mangrove species found at the front mangrove area:

The Nyireh Batu (Xylocarpus moluccensis), a rarer relative of the more commonly seen Nyireh Bunga (Xylocarpus granatum) which is also found here, is doing surprisingly well along the boardwalk. The various Xylocarpus species are usually called Mangrove Cannonball for their round fruits, which break upon drying or when they hit the ground, and the seeds are dispersed by water.

The Atlas Moth (Attacus atlas) appear to like feeding on the leaves of the Niyreh Batu (and various other true and back mangrove plant species). This moth is the biggest moth in the world in terms of total wing surface area, and its wingspan is also one of the widest, up to 30cm.

The Buta-buta (Excoecaria agallocha) usually occurs towards the landward side of the true mangrove habitat. It is also called "Blind-your-eyes", has poisonous white sap which can cause blistering and blindness. The tree is also deciduous, and the leaves turn yellow, orange or even reddish before they are shed.

The blind-your-eyes tree can often be found growing on mud lobster mounds, which appears like little volcanoes among the mud. Mud Lobsters (Thalassina sp.) eat tiny organic particles in the mud, and as they process the huge amounts of mud and sand to seek food, the processed mud is piled around their burrows, forming the little "volcano-like" structures. Mud lobsters play an important role of bringing nutrient-rich soil to the surface. Many other plants and animals live in or on mud lobster mounds too, attracted by the nutrients, and also, higher ground and free lodging (burrow made by the mud lobster) to get away from the sea water.

The Teruntum Merah (Lumnitzera littorea) also occurs here. It has pretty red flowers, and even the young branches are reddish in colour. The wood is hard and extremely durable, and is used for the building of bridges, wharves, cart axles, flooring and sleepers. It has a rose-like scent, making it popular as a cabinet timber.

An animal commonly seen on mud lobster mounds is the Tree-climbing Crab (Episesarma sp.), which usually dig burrows into the mounds or at the base of trees. During high tide, you may encounter many of them climbing up to trees to avoid the predatory fishes in the water. Tree-climbing crabs are primarily leaf-eaters. They are also called vinegar crabs, because the Teochews are known to pickle this crab in black sauce with vinegar.

The Mangrove Pitta (Pitta megarhyncha) can occasionally be seen foraging among the mud lobster mounds, in both the true and back mangrove habitats. It has been observed to feed on slugs, snails and small crabs. It is a rare resident in Singapore, and globally near-threatened due to loss of habitat.

Moving seaward, the Nipah Palm (Nypa fruticans) is the only true mangrove palm in Singapore. Also called the Attap Palm, its seed (called "attap chee") is edible is added to several local desserts, such as the ice kacang. The leaves are used for thatching. A sweet syrup can be extracted from the flower stalk in large quantities and made into palm sugar, or used in the production of alcohol (including ‘toddy’), sugar and vinegar.

The Bakau Minyak (Rhizophora apiculata), like other Rhizophora species, has prop roots and stilt roots at the lower part of the tree. The wood is hard and heavy, and is used for making scaffolding and furniture. It is widely used for making charcoal. This tree is often planted along fish ponds to protect the bunds. It can occur quite close to the sea.

Among the roots and in the mud, the Orange Mud Crab (Scylla olivacea), which is the mud crab often used in the popular "Chilli Crab" dish. These crabs usually feed on clams which they crush with their powerful claws. They are very valuable in the local market, and are used in various popular local dishes.

The Lenggadai (Bruguiera parviflora) is rather uncommon in other mangroves, but there is a good population at Pasir Ris along the boardwalk. The wood from this tree produces good charcoal and pulp. It is usually used as firewood or for mining and making fishing-stakes. The germinating seedling is sometimes eaten as a vegetable.

Another common mangrove tree here nearer to the seaward side is the Perepat (Sonneratia alba). Like other Sonneratia species, it has conical roots protruding from the ground. The fruits and leaves are edible, while the wood is used for various construction purposes, such as the construction of buildings, bridges, boats, wooden tools and furniture.

There is a nesting colony of Grey Herons (Ardea cinerea) on some of the Perepat trees along Sungei Tampines. One of the biggest bird in Singapore, it can reach heights of about 1m, and has a light grey plumage. The long legs enable it to wade in shallow water or among tall grasses to hunt small animals, such as fishes, amphibians, reptiles, insects, crustaceans and even small mammals and birds.

The Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax) is often seen here too. This is a nocturnal bird, and usually roost in trees in the day. It has gotten its common name from its black crown. This heron lacks the long neck of the previous species (though the neck can stretch quite far out), but is still fairly tall (about 65cm). Like the other herons, it feeds on small animals.

Another rather common mangrove tree here is the Ceriops zippeliana, which was only discovered to be a new species in recent studies. The Ceriops, Rhizophora and Bruguiera mangrove trees demonstrate vivipary, a condition whereby the young plant within the seed grows first to break through the seed coat then out of the fruit wall while still attached to the parent plant. Since the mangrove habitat is a very harsh environment, these plants have adapted such that the parent plants prepare their young as much as possible to increase their chances of survival. The seedlings are dispersed by water. They float horizontally for a few weeks, during which the root (lower part) will absorb water and become heavier, eventually causing the seedlings to tip and float vertically. As the tide goes down, the vertically-oriented seedling will sink into the mud or other suitable substrates. Most of the seedlings, however, end up being washed ashore or eaten by animals.

The Rhizophora, Bruguiera and Ceriops, together with the Perepet also deal with the saline conditions in a similar manner. They can selectively absorb only certain ions from the sea water through a process called ultrafiltration. But this process is not 100% effective, and some salt still gets into the trees, and will be removed by transpiration of the leaf surfaces or accumulated in old leaves.

The Api-api Putih (Avicennia alba) and other Avicennia species, on the other hand, not only exclude salt from entering the plant, but has salt glands on the leaves to excrete part of the remaining quantity of salt. "Api-api" means "fire-fire" or "firefly" in Malay, as some Avicennia species are noted to attract fireflies.

On the trunks of these mangrove trees, various snails, such as the conical Chut-chut (Cerithidea spp.) and the round Articulate Nerites (Nerita articulata) above. The Chut-chut got its name from the way the cooked snails are eaten - by sucking the content out from the shell, making a "chut-chut" sound. The Articulate Nerites got their names from their shells' appearance - the shell looks as if it consists of sections united by joints (meaning of articulate in anatomy). Both feed on algae.

Many fishes occurs in the mangroves, and the Giant Mudskipper (Periophthalmodon schlosseri) is one of them. This is the largest mudskipper species in Singapore. It is able to survive out of water by holding water in its mouth and gill chambers. It can breathe through its skin when it is wet too. Being a rather aggressive fish, it feeds on other small animals, such as crabs or worms.

The Spotted Archerfish (Toxotes chatareus) is yet another fish that can be seen here. This fish feeds on insects by shooting them down with water. They may also jump out of the water to get their prey if they are near enough.

And if there are fishes, there will be kingfishers! The Collared Kingfisher (Todiramphus chloris) is one of the commonest kingfisher in Singapore. Most of the time, they could be well-hidden among the foliage, but you could often still hear the distinctive cackling call. They do not just feed on fish though, but insects as well.

Towards the end and beginning of the year, migratory waders can also be seen here. The photo above shows two Whimbrels (Numenius phaeopus). They feed on worms in the mud by digging them out with their long beaks.

Pasir Ris Mangrove is perhaps also one of the most convenient place on mainland Singapore to see the Dog-faced Water Snake (Cerberus rynchops). This snake is mildly venomous and feed on small fishes. It sometimes hunt other small animals too. It is usually easier to see them at night, in the early morning or late afternoon when it is cooler and darker.

Conserving Pasir Ris Mangrove Forest

The entire Pasir Ris Park is currently managed by NParks, but it is still very vulnerable to possible development plans in future. There are also problems of poachers who collect plants and animals without an NParks permit, and anglers not disposing disused fishing lines properly. The latter is especially an issue and many animals got entangled in the lines and either starve to death or get badly wounded. There is also the rubbish issue, as the park users may not have disposed their waste properly and animals may end up eating or getting trapped in them.

As such, it is important that Singaporeans visiting this park should behave in a more responsible manner. It is important for Singaporeans to learn more about our various nature spots, the issues they face, so that we can better protect what is left. Hence, I always encourage those who visit my blog to read up more about our natural heritage from books or online resources.

It is also important that nature lovers do share your experience with their friends so that more people get to know and visit Chek Jawa. And if time permits, become a volunteer to help with conducting guided walks here!

At the end of the day, we also hope that more Singaporeans can feedback to the government if they enjoy visiting our nature spots and hope to preserve them as they are, so that the authorities will know that we do value our natural heritage and these nature spots will be protected.