A bivalve (phylum Mollusca, class Bivalvia) is a soft-bodied animal with a two-part shell that is usually large enough to enclose the whole animal. The two parts (or valves) of the shell are connected by a hinge, which is essentially a flexible ligament, and interlocking "teeth" on each valve. Like other shelled molluscs, the shells of bivalves are composed of calcium carbonate.

Unlike most other molluscs, bivalves have no head or radula (a tongue-like structure for feeding). They are mostly filter-feeders, using their modified gills to filter plankton from the water. These gills are used for breathing as well.

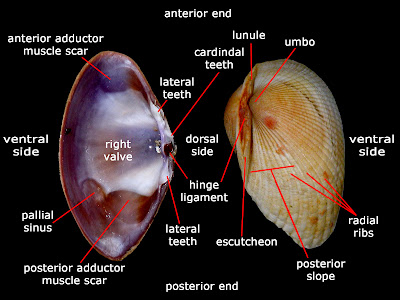

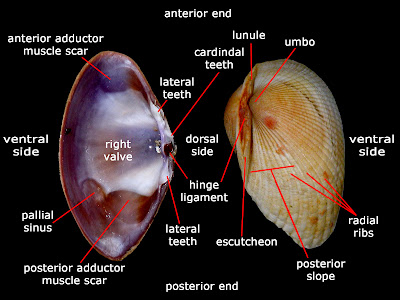

Although we can find introduced freshwater bivalves in some of our freshwater habitats, the native bivalves recorded in Singapore are are found in the marine environment. To differentiate one species from another, it is important to know the parts of a bivalve's shell first. I have a diagram here highlighting some of the parts of a bivalve's shell that is important to help with identifying them:

You can click on the above picture to for a bigger image, and a clearer look at the anatomy of a bivalve's shell.

Bivalves recorded from Singapore are largely from three subclasses: Protobranchia, Heterodonta, and Pteriomorphia.

SUBCLASS PROTOBRANCHIA

The protobranchs are primitive small-sized marine bivalves with very small and simple plate-like gills which are used for respiration only, unlike most other bivalves which use their gills for both filter-feeding and respiration. Instead, they posses large labial palps (a pair of fleshy appendages at the mouth) for deposit feeding. Protobranchs also have a taxodont hinge - the hinge is composed of many small, similar teeth. The interior of the shell is nacreous for some species. Unfortunately, I still have not photographed any protobranchs in Singapore yet.

SUBCLASS HETERODONTA

The heterodonts (subclass heterodonta) have elaborate, folded leaf-like gills used for both respiration and feeding. The shells have a complex hinge with small numbers of different types of teeth. The shell is never nacreous. They are mostly burrowers (though there are exceptions), and usually possess well-developed siphons, comprising an incurrent siphon which water enters with planktonic food particles to be filtered by the gills, and an excurrent siphon which filtered water is expelled.

Family Cardiidae

Cardiid bivalves (family Cardiidae) traditionally consists of only the true cockles, but recent studies shown that the giant clams (previously placed in a family of their own, Tridacnidae) should be part of this family as well. Members of this family typically have strong, compact and completely symmetrical shells which appear heart-shaped when viewed from the anterior end due to the prominent umbones. The shell usually has obvious radial ribs, and on the inside, there are two cardinal teeth in each valve and no pallial sinus. They have short siphons, external ligaments, and most of the motile species have a well-developed, sickle-shaped foot, which allows them to move in short leaps over the substrate. Many species harbour symbiotic algae, which photosynthesize and share the food produced with the host bivalves, in exchange for shelter and nutrients (the metabolic waste of the host). Some species are collected for food or for making shellcraft.

Family Veneridae

Venerid bivalves (family Veneridae), usually called Venus clams, have a complex tooth structure with three divergent teeth in the hinge, and a well-developed sinus at the pallial line. The shells are symmetrical, and the escutcheon and lunule are very well-developed. The shapes of the various members are very variable, ranging from circular to triangular from side view, or ovate to heart-shaped when viewed from the anterior end. Some species may have obvious radial ribs or concentric ridges. As such, some species may be mistaken with members from the previous family. Many members have complicated patterns and beautiful colours. Venerid bivalves are mostly free-living, and some species may burrow. They have a folded gill structure which is developed for filtering small food particles - typical of members from this family and other related families. The foot is tongue-like. Many species are collected for food.

Family Petricolidae

Petricolid bivalves (family Petricolidae) were previously placed under the family Veneridae, though genetic studies have placed them as a separate family since the year 2010. The symmetrical shell is usually ovate, thin, and white. The hinge has two or three cardinal teeth, but there is no lateral tooth. They have a deep pallial sinus, long siphons and a narrow foot. The umbones are obviously protruding, with concentric growth lines expanding from the dorsal end to the anterior end. The animal is usually free-living, but is often found boring into clay, soft rocks or corals.

Family Lucinidae

Lucinid bivalves (family Lucinidae) generally have rounded to subtrapezoidal shells. The umbones are small and low, while the lunule is small and often asymmetrical. The outer surface is often marked with concentric and/ or radial components. The hinge usually has two cardinal teeth, with a few lateral teeth in each valve, though some or all the teeth may be reduced or even absent. The ligament is external and somewhat sunken. In the shell interior, the anterior adductor muscle scar is narrow and elongate, often with a lobe detached from the pallial line towards the ventral side, while the posterior scar appears irregularly shaped. There is no pallial sinus. It has a long, worm-like foot. The inhalant siphon is usually replaced by a rounded anterior tube lined with mucus, separate from the exhalant siphon. Many species house symbiotic, sulphur-oxydizing chemautotrophic bacteria in their thick gills, which provide food for the clams in return for shelter.

Family Mactridae

Mactrid Clams (family Mactridae) are mostly burrowers, and hence their shells are usually quite strong. The shell is symmetrical, and the surface is smooth and marked with concentric growth lines. The cardinal teeth are much reduced, and lateral teeth are usually present. The two adductor muscle scars are usually subequal, and there is a pallial line with a well-developed sinus. The siphon tubes are united and fringed at the tips. The foot is usually wedge-shaped. Most species live in shallow waters, and with their large sizes, they are extensively collected for food.

Family Cyrenidae

Cyrenid bivalves (family Cyrenidae) are found in fresh or brackish water, and in Singapore, the native species are found in the mangroves. The symmetrical shells are somewhat sub-triangular, with two or three cardinal teeth and several laterals. The surface is usually marked with concentric growth lines. The foot is large and strong, while the siphon is short. Cyrenid clams are free-living with no byssus. Many species are collected for food.

Family Tellinidae

Tellinid bivalves (Family Tellinidae) usually appear compressed and translucent. The hinge has two cardinal teeth, and the ligament is external. The pallial sinus is deep, and the foot is long and extensible. The siphons are long, slender and separate. The anterior adductor muscle scar is somewhat elongated, while the posterior one is somewhat rounded or quadrate. The have a deep pallial sinus. Tellinid bivalves are mostly found just below the surface of sandy or muddy substrates. Many species are marked with beautiful colours and patterns. In some species one of the valves may be flatter than the other. Many species are collected for shellcraft.

Family Semelidae

Semelid bivalves (Family Semelidae) generally have thin shells with a wave-like fold towards the posterior end. The hinge has two cardinal teeth and lateral teeth. The hinge ligament has two parts - a short external posterior ligament and an internal ligament (called the resilium) located between the two valves behind the umbones in a small pit of hinge plates. On the shell interior, each valve has two adductor muscle scars, and a pallial line with a deep sinus. The siphons are long and divergent.

Family Corbulidae

Corbulid clams (Family Corbulidae) are usually small-sized with a simple hinge formed by a recurved tooth fitting into a socket. The shells may be ovate, oblong or triangular, usually marked with concentric ridges. The posterior end usually tapers to a truncate or angular tip. The right valve is usually bigger and overlaps the left shell, and depending on the species teh two valves may differ in shape and ornamentation. It has short, united siphons which are fringed. They are usually found living in sandy or muddy substrates, or attached to hard substrates.

Family Chamidae

Chamid bivalves (family Chamidae), commonly called jewel boxes or jewel box clams, superficially resemble oysters as most species (there are exceptions) are cemented to hard substrates such as rocks or other shells. The shells are thick, with a somewhat round outline but irregularly shaped. They are usually covered with short spikes or leaf-like structures, trapping sediment and algae. They are thus often overlooked and hard to identify in the field. The ligament is external, while the hinge thick and arched with a few large curved teeth and corresponding sockets. The shell interior is porcelaneous, and each valve has two large, subequal and ovate adductor muscles scars. There is a pallial line without a sinus. Since they are stuck to hard substrates and need not move around, they have a very reduced foot. They are collected for food and the shells are sometimes used as lime material or for shellcraft.

Family Galeommatidae

Galeommatid bivalves (family Galeommatidae) are usually small and found under rocks or coral rubble. They have very reduced and flexible shells, mostly enclosed within the well-developed mantle. The hinge is irregular, with tiny cardinal teeth and somewhat obscure lateral teeth. Some species may behave like slugs, sliding over the substrate using their well-developed foot, while others can move in short leaps.

Family Solenidae

Solenid bivalves (family Solenidae) typically have elongated shells, appearing somewhat rectangular in shape. The two valves cannot close completely, leaving an opening at both the anterior and posterior ends. The hinge ligament is external, while the hinge has two or three small teeth. The umbones are not obvious, and the exterior of the shell is usually marked with concentric growth lines. The edges of the valves are very sharp, and hence they are often called razor clams. They have a very strong, cylindrical foot, which allows them to burrow quickly into the sand vertically. The anterior adductor muscle scar is usually larger than the posterior one. The pallial sinus is relatively shallow. The siphons can be short or long, and are fused, at least at the base. They are often collected for food.

Family Clavagellidae

Clavagellid bivalves (family Clavagellidae) have an interesting life cycle. They begin their life like other bivalves with two separate valves, but as they mature, they will burrow into the sandy or muddy substrates and build a tube. The valves will be reduced to a pair of round structures stuck to one side of the tube surface. The anterior end of the tube faces downwards, with a cap-like structure marked with numerous tiny holes, resembling the sieve of a water pot, and hence the common name "watering pot shell". The posterior end will stick out of the substrate, with an opening which allows the animal to filter feed.

Family Teredinidae

Teredinid bivalves (family Teredinidae), more commonly called shipworms, are wood-boring, marine bivalves that exist with nitrogen-fixing bacteria which provide them with enzymes to digest the wood they have consumed. Due to the burrows they create as they feed, they cause damage to wooden structures, such as jetties, ships and pillars of bridges. Shipworms begin their life as free-swimming juveniles with eyes for a brief period, which eventually disappear after they settle on submerged wood, which they will bore into using the foot and possibly also by scraping with the valves, creating tunnels in the wood in the process. The animals themselves appear worm-like, and most line all or part of their burrows with a layer of calcareous tube. When the wood gets eroded away, the tubes get exposed and may be mistaken for tube worms or worm snails.

SUBCLASS PTERIOMORPHIA

The pteriomorphs (subclass Pteriomorphia) also have elaborate, folded leaf-like gills used for both respiration and feeding. The hinges on the shells, however, are taxodont (with a few reduced teeth or no teeth). Some have a nacreous shell interior. Many pteriomorphs are sessile as adults, living attached to rocks and other hard structures. Others may be free-living or shallow burrowers. They may have a short siphon, or no siphon at all. The foot and anterior adductor may be very reduced or lost in many species.

Family Arcidae

Arkshells (family Arcidae) are characterised by their hooked umbones and straight-edged hinge with a series of small comb-like teeth. The ligament is external, and many have byssal threads to anchor themselves to hard substrates. The shapes tend to appear somewhat rectangular, and the surface is marked with radial ribs and often covered with hair-like structures. In the shell interior, two subequal adductor muscle scars and a pallial line without a sinus can be seen. Interestingly, they have hemoglobin, an oxygen transport pigment, dissolved in both the blood and tissues, colouring the animal reddish. This is unlike most other bivalves, which absorbs oxygen directly from the water into the tissues. In Singapore, they are often mistaken and wrongly identified as cockles, which are from the family Cardiidae, as both families possess radial ribs. The "See Hum" which is well-loved by Singaporeans, either boiled or added to laksa and char kuay teow, is actually an ark shell, but often called "Blood Cockles" in Singapore.

Family Pectinidae

Scallops (family Pectinidae) generally have fan-shaped shells with two fin-like extensions (anterior and posterior ears) at the hinge, one on each side of the "fan", hence forming a straight and extended line at the hinge. The surface is marked with radial ribs. They have a powerful adductor muscle, a toothless hinge with a socket-like arrangement and the ligament is mostly internal. They only have the posterior adductor muscle scar, and have a pallial line but no sinus. Their foot is greatly reduced, and they do not have siphons. To feed, they clap their valves to generate a current so as to filter plankton from the water. Scallops possess tiny but well-developed eyes along the edge of their fleshy mantle. They are able to produce byssus to anchor themselves to hard surfaces, but most species will cast off their byssus as they mature and become free-living. Some species are able to swim by clapping their valves to expel water around the hinge, hence propelling them in the direction of the valve opening. Many scallops are collected for food, and most of the time, only the huge adductor muscle is eaten.

Family Limidae

File clams (family Limidae) are also fan-shaped, but lack the fin-like extensions. They only have the posterior adductor muscle scar, and a pallial line but no sinus. The foot can range from short and thick to long and narrow. Most species remain attached to the substrates with byssal threads or hide under rocks, though several are known to be free-living. Some species can swim by clapping their valves, much like the scallops, but instead of moving in the direction of the valve opening, they usually go in the direction of the hinge. They possess long sticky tentacles, which can be vibrantly coloured and break off easily to confuse predators. The shell surface is usually very rough, and hence the common name "file clam".

Family Pinnidae

Pinnid bivalves (family Pinnidae) are usually called pen shells (for their pointed tips) or fan shells (for the shell's fan-like or narrowly triangular shape). The shell is very thin and fragile, the hinge is toothless. The interior of the shell has a thin pearly layer towards the anterior half of the valves. The two adductor muscle scars are unequal, with the anterior one relatively small. There is no pallial sinus. The foot is long, conical and grooved. It has no siphon. These bivalves are usually half-buried in the sand/mud, anchored to their position by numerous byssal threads. The byssal threads of some pen shells are in fact used to weave into sea silk, a very valuable fabric which is extremely light and warm. Species found in the region are often collected for food.

Family Placunidae

Placunid bivalves (family Placunidae) are often called "window pane shells", as they are collected, polished, and pasted together to make into window panes or lamp shades in the region. The shells are very much flattened, and have a pearly surface. The hinge is almost straight with no teeth and no byssus. The ligament is usually internal, forming an inverted V-shaped structure. The shells have a single, centrally located posterior adductor muscle scar, and no pallial sinus. The foot is long, narrow and cylindrical.

Family Anomiidae

Anomiid bivalves (Family Anomiidae), or jingle shells, usually have very thin and somewhat flattened shells. They are usually attached to rocks, shell fragments, or even mangrove trees with their large and calcified byssus. There is a large and deep notch for the byssus in the lower valve near the hinge. The foot is dwarfed, finger-like, and grooved. Most shells have very pretty, pearly surfaces, and are hence collected for shellcraft.

Family Malleidae

Malleid bivalves (Family Malleidae) are called "hammer oysters", as the shells of many species appear "T"-shaped, though there are many exceptions. The hinge is narrow and held by an oblique ligament rather than teeth, and the shell is partially nacreous. The umbones are not conspicuous. The interior of each valve only has the posterior adductor muscle scar, and a pallial line without a sinus. The adults may or may not have byssal threads. The foot is divided into two unequal parts. They do not have a siphon. They can be free-living, partially buried in sandy substrates, or attached to hard substrates, or embedded in sponges.

Family Pteriidae

Pteriid bivalves (family Pteriidae) generally have somewhat compressed shells and a straight dorsal margin, with a wing-like ear on each or both ends. Members previously group under the family Isognomonidae (commonly called "leaf oysters") are recently included under this family after phylogenetic studies. The left valve of the shell is usually a little more inflated than the right valve, and there is a strong byssal notch anteriorly. The exterior surface of the shell often appears scaly or lamellate. The umbones are small, and the hinge is narrow and usually toothless. The interior of the shell is usually nacreous, with one large posterior adductor muscle scar and a pallial line but no sinus. The foot is small and grooved, with a strong byssus. They do not have any siphon. Many pearl oysters are from this family, and they have been exploited since ancient times for their ability to produce pearls. Some species may be confused with members of the previous family.

Family Mytilidae

Mussels (Family Mytilidae) generally have pear-shaped shells, and are attached to the substrates with strong byssus. Most are found on rocky and other hard substrates, but some have adapted to living in sandy or muddy substrates as well, with some species building nest covering huge areas of shallow sea beds. The hinge has no or reduced teeth, and the ligament is long and external. The interior of the shell is pearly. The anterior adductor muscle scar is small or sometimes absent in the adult, while the posterior adductor scar is large. The shell has a pallial line but without a sinus. The foot is long and grooved. The siphons are either very reduced or absent. Many species are economically important, being edible and abundant.

Family Gryphaeidae

Gryphaeid bivalves (Family Gryphaeidae) are often called "honeycomb oysters" because under a magnifying lens, the shell structure exhibits a honeycomb-like appearance. The shells, often irregularly shaped, can grow to huge sizes of about 30cm, and hence they are sometimes mistaken to be giant clams. Both valves are convex with large, irregular radial ribs, giving the opening on the ventral side a zigzag appearance. The hinge has no tooth. In the shell interior, there is only a large and rounded posterior adductor muscle scar placed closer to the hinge, but no anterior one. The pallial line is present, but the sinus is obscure to absent. They have no siphon. Some species are collect for food.

Family Ostreidae

Ostreid bivalves (family Ostreidae), also called the "true oysters", are commercially important around the world as food oysters. The shell is hard and often irregularly shaped, and cemented to the substrate by the left valve. The right valve usually appears more flattened, with a protruding fringe beyond the shell margin. The hinge has no tooth, and the shell interior is porcelaneous. It only has the posterior adductor muscle scar, generally, but unlike the previous family it is positioned nearer to the ventral side than to the hinge. It has a pallial line without a sinus, obscure to absent. The animal has no byssus, foot or siphon. Interestingly, both egg-bearing (oviparous) and larvae-bearing (larviparous) species can be found within the family. The larviparous species are able to change sex in the same individual, while the oviparous species may produce either more male or female gametes depending on the nutrients available or environmental temperature.

Family Spondylidae

Spondylid bivalves (family Spondylidae), commonly called "thorny oysters", are more closely related to scallops genetically. The shell is usually stout and very variable in shape, but all are cemented to substrate by the right valve, which is more convex than the left valve. The hinge has two strongly curved teeth and two deep sockets in each valve. The hinge line is straight, and often with a small ear on either side of the umbo. The ligament is mostly internal. The outer surface is usually brightly coloured and marked with numerous thin and spiny or scaly protrusions. The interior of the shell is porcelaneous. Spondylid bivalves have a single, rounded posterior adductor muscle scar, but lacks the anterior muscle scar. The pallial line is present, but without a sinus. The foot is reduced, and the siphon is absent. The adult lacks a byssus. Many species are collected for food.

References

Unlike most other molluscs, bivalves have no head or radula (a tongue-like structure for feeding). They are mostly filter-feeders, using their modified gills to filter plankton from the water. These gills are used for breathing as well.

Although we can find introduced freshwater bivalves in some of our freshwater habitats, the native bivalves recorded in Singapore are are found in the marine environment. To differentiate one species from another, it is important to know the parts of a bivalve's shell first. I have a diagram here highlighting some of the parts of a bivalve's shell that is important to help with identifying them:

You can click on the above picture to for a bigger image, and a clearer look at the anatomy of a bivalve's shell.

Bivalves recorded from Singapore are largely from three subclasses: Protobranchia, Heterodonta, and Pteriomorphia.

SUBCLASS PROTOBRANCHIA

The protobranchs are primitive small-sized marine bivalves with very small and simple plate-like gills which are used for respiration only, unlike most other bivalves which use their gills for both filter-feeding and respiration. Instead, they posses large labial palps (a pair of fleshy appendages at the mouth) for deposit feeding. Protobranchs also have a taxodont hinge - the hinge is composed of many small, similar teeth. The interior of the shell is nacreous for some species. Unfortunately, I still have not photographed any protobranchs in Singapore yet.

SUBCLASS HETERODONTA

The heterodonts (subclass heterodonta) have elaborate, folded leaf-like gills used for both respiration and feeding. The shells have a complex hinge with small numbers of different types of teeth. The shell is never nacreous. They are mostly burrowers (though there are exceptions), and usually possess well-developed siphons, comprising an incurrent siphon which water enters with planktonic food particles to be filtered by the gills, and an excurrent siphon which filtered water is expelled.

Family Cardiidae

Cardiid bivalves (family Cardiidae) traditionally consists of only the true cockles, but recent studies shown that the giant clams (previously placed in a family of their own, Tridacnidae) should be part of this family as well. Members of this family typically have strong, compact and completely symmetrical shells which appear heart-shaped when viewed from the anterior end due to the prominent umbones. The shell usually has obvious radial ribs, and on the inside, there are two cardinal teeth in each valve and no pallial sinus. They have short siphons, external ligaments, and most of the motile species have a well-developed, sickle-shaped foot, which allows them to move in short leaps over the substrate. Many species harbour symbiotic algae, which photosynthesize and share the food produced with the host bivalves, in exchange for shelter and nutrients (the metabolic waste of the host). Some species are collected for food or for making shellcraft.

Family Veneridae

Venerid bivalves (family Veneridae), usually called Venus clams, have a complex tooth structure with three divergent teeth in the hinge, and a well-developed sinus at the pallial line. The shells are symmetrical, and the escutcheon and lunule are very well-developed. The shapes of the various members are very variable, ranging from circular to triangular from side view, or ovate to heart-shaped when viewed from the anterior end. Some species may have obvious radial ribs or concentric ridges. As such, some species may be mistaken with members from the previous family. Many members have complicated patterns and beautiful colours. Venerid bivalves are mostly free-living, and some species may burrow. They have a folded gill structure which is developed for filtering small food particles - typical of members from this family and other related families. The foot is tongue-like. Many species are collected for food.

Family Petricolidae

Petricolid bivalves (family Petricolidae) were previously placed under the family Veneridae, though genetic studies have placed them as a separate family since the year 2010. The symmetrical shell is usually ovate, thin, and white. The hinge has two or three cardinal teeth, but there is no lateral tooth. They have a deep pallial sinus, long siphons and a narrow foot. The umbones are obviously protruding, with concentric growth lines expanding from the dorsal end to the anterior end. The animal is usually free-living, but is often found boring into clay, soft rocks or corals.

Family Lucinidae

Lucinid bivalves (family Lucinidae) generally have rounded to subtrapezoidal shells. The umbones are small and low, while the lunule is small and often asymmetrical. The outer surface is often marked with concentric and/ or radial components. The hinge usually has two cardinal teeth, with a few lateral teeth in each valve, though some or all the teeth may be reduced or even absent. The ligament is external and somewhat sunken. In the shell interior, the anterior adductor muscle scar is narrow and elongate, often with a lobe detached from the pallial line towards the ventral side, while the posterior scar appears irregularly shaped. There is no pallial sinus. It has a long, worm-like foot. The inhalant siphon is usually replaced by a rounded anterior tube lined with mucus, separate from the exhalant siphon. Many species house symbiotic, sulphur-oxydizing chemautotrophic bacteria in their thick gills, which provide food for the clams in return for shelter.

Family Mactridae

Mactrid Clams (family Mactridae) are mostly burrowers, and hence their shells are usually quite strong. The shell is symmetrical, and the surface is smooth and marked with concentric growth lines. The cardinal teeth are much reduced, and lateral teeth are usually present. The two adductor muscle scars are usually subequal, and there is a pallial line with a well-developed sinus. The siphon tubes are united and fringed at the tips. The foot is usually wedge-shaped. Most species live in shallow waters, and with their large sizes, they are extensively collected for food.

Family Cyrenidae

Cyrenid bivalves (family Cyrenidae) are found in fresh or brackish water, and in Singapore, the native species are found in the mangroves. The symmetrical shells are somewhat sub-triangular, with two or three cardinal teeth and several laterals. The surface is usually marked with concentric growth lines. The foot is large and strong, while the siphon is short. Cyrenid clams are free-living with no byssus. Many species are collected for food.

Family Tellinidae

Tellinid bivalves (Family Tellinidae) usually appear compressed and translucent. The hinge has two cardinal teeth, and the ligament is external. The pallial sinus is deep, and the foot is long and extensible. The siphons are long, slender and separate. The anterior adductor muscle scar is somewhat elongated, while the posterior one is somewhat rounded or quadrate. The have a deep pallial sinus. Tellinid bivalves are mostly found just below the surface of sandy or muddy substrates. Many species are marked with beautiful colours and patterns. In some species one of the valves may be flatter than the other. Many species are collected for shellcraft.

Family Semelidae

Semelid bivalves (Family Semelidae) generally have thin shells with a wave-like fold towards the posterior end. The hinge has two cardinal teeth and lateral teeth. The hinge ligament has two parts - a short external posterior ligament and an internal ligament (called the resilium) located between the two valves behind the umbones in a small pit of hinge plates. On the shell interior, each valve has two adductor muscle scars, and a pallial line with a deep sinus. The siphons are long and divergent.

Family Corbulidae

Corbulid clams (Family Corbulidae) are usually small-sized with a simple hinge formed by a recurved tooth fitting into a socket. The shells may be ovate, oblong or triangular, usually marked with concentric ridges. The posterior end usually tapers to a truncate or angular tip. The right valve is usually bigger and overlaps the left shell, and depending on the species teh two valves may differ in shape and ornamentation. It has short, united siphons which are fringed. They are usually found living in sandy or muddy substrates, or attached to hard substrates.

Family Chamidae

Chamid bivalves (family Chamidae), commonly called jewel boxes or jewel box clams, superficially resemble oysters as most species (there are exceptions) are cemented to hard substrates such as rocks or other shells. The shells are thick, with a somewhat round outline but irregularly shaped. They are usually covered with short spikes or leaf-like structures, trapping sediment and algae. They are thus often overlooked and hard to identify in the field. The ligament is external, while the hinge thick and arched with a few large curved teeth and corresponding sockets. The shell interior is porcelaneous, and each valve has two large, subequal and ovate adductor muscles scars. There is a pallial line without a sinus. Since they are stuck to hard substrates and need not move around, they have a very reduced foot. They are collected for food and the shells are sometimes used as lime material or for shellcraft.

Family Galeommatidae

Galeommatid bivalves (family Galeommatidae) are usually small and found under rocks or coral rubble. They have very reduced and flexible shells, mostly enclosed within the well-developed mantle. The hinge is irregular, with tiny cardinal teeth and somewhat obscure lateral teeth. Some species may behave like slugs, sliding over the substrate using their well-developed foot, while others can move in short leaps.

Family Solenidae

Solenid bivalves (family Solenidae) typically have elongated shells, appearing somewhat rectangular in shape. The two valves cannot close completely, leaving an opening at both the anterior and posterior ends. The hinge ligament is external, while the hinge has two or three small teeth. The umbones are not obvious, and the exterior of the shell is usually marked with concentric growth lines. The edges of the valves are very sharp, and hence they are often called razor clams. They have a very strong, cylindrical foot, which allows them to burrow quickly into the sand vertically. The anterior adductor muscle scar is usually larger than the posterior one. The pallial sinus is relatively shallow. The siphons can be short or long, and are fused, at least at the base. They are often collected for food.

Family Clavagellidae

Clavagellid bivalves (family Clavagellidae) have an interesting life cycle. They begin their life like other bivalves with two separate valves, but as they mature, they will burrow into the sandy or muddy substrates and build a tube. The valves will be reduced to a pair of round structures stuck to one side of the tube surface. The anterior end of the tube faces downwards, with a cap-like structure marked with numerous tiny holes, resembling the sieve of a water pot, and hence the common name "watering pot shell". The posterior end will stick out of the substrate, with an opening which allows the animal to filter feed.

Family Teredinidae

Teredinid bivalves (family Teredinidae), more commonly called shipworms, are wood-boring, marine bivalves that exist with nitrogen-fixing bacteria which provide them with enzymes to digest the wood they have consumed. Due to the burrows they create as they feed, they cause damage to wooden structures, such as jetties, ships and pillars of bridges. Shipworms begin their life as free-swimming juveniles with eyes for a brief period, which eventually disappear after they settle on submerged wood, which they will bore into using the foot and possibly also by scraping with the valves, creating tunnels in the wood in the process. The animals themselves appear worm-like, and most line all or part of their burrows with a layer of calcareous tube. When the wood gets eroded away, the tubes get exposed and may be mistaken for tube worms or worm snails.

SUBCLASS PTERIOMORPHIA

The pteriomorphs (subclass Pteriomorphia) also have elaborate, folded leaf-like gills used for both respiration and feeding. The hinges on the shells, however, are taxodont (with a few reduced teeth or no teeth). Some have a nacreous shell interior. Many pteriomorphs are sessile as adults, living attached to rocks and other hard structures. Others may be free-living or shallow burrowers. They may have a short siphon, or no siphon at all. The foot and anterior adductor may be very reduced or lost in many species.

Family Arcidae

Arkshells (family Arcidae) are characterised by their hooked umbones and straight-edged hinge with a series of small comb-like teeth. The ligament is external, and many have byssal threads to anchor themselves to hard substrates. The shapes tend to appear somewhat rectangular, and the surface is marked with radial ribs and often covered with hair-like structures. In the shell interior, two subequal adductor muscle scars and a pallial line without a sinus can be seen. Interestingly, they have hemoglobin, an oxygen transport pigment, dissolved in both the blood and tissues, colouring the animal reddish. This is unlike most other bivalves, which absorbs oxygen directly from the water into the tissues. In Singapore, they are often mistaken and wrongly identified as cockles, which are from the family Cardiidae, as both families possess radial ribs. The "See Hum" which is well-loved by Singaporeans, either boiled or added to laksa and char kuay teow, is actually an ark shell, but often called "Blood Cockles" in Singapore.

Family Pectinidae

Scallops (family Pectinidae) generally have fan-shaped shells with two fin-like extensions (anterior and posterior ears) at the hinge, one on each side of the "fan", hence forming a straight and extended line at the hinge. The surface is marked with radial ribs. They have a powerful adductor muscle, a toothless hinge with a socket-like arrangement and the ligament is mostly internal. They only have the posterior adductor muscle scar, and have a pallial line but no sinus. Their foot is greatly reduced, and they do not have siphons. To feed, they clap their valves to generate a current so as to filter plankton from the water. Scallops possess tiny but well-developed eyes along the edge of their fleshy mantle. They are able to produce byssus to anchor themselves to hard surfaces, but most species will cast off their byssus as they mature and become free-living. Some species are able to swim by clapping their valves to expel water around the hinge, hence propelling them in the direction of the valve opening. Many scallops are collected for food, and most of the time, only the huge adductor muscle is eaten.

Family Limidae

File clams (family Limidae) are also fan-shaped, but lack the fin-like extensions. They only have the posterior adductor muscle scar, and a pallial line but no sinus. The foot can range from short and thick to long and narrow. Most species remain attached to the substrates with byssal threads or hide under rocks, though several are known to be free-living. Some species can swim by clapping their valves, much like the scallops, but instead of moving in the direction of the valve opening, they usually go in the direction of the hinge. They possess long sticky tentacles, which can be vibrantly coloured and break off easily to confuse predators. The shell surface is usually very rough, and hence the common name "file clam".

Family Pinnidae

Pinnid bivalves (family Pinnidae) are usually called pen shells (for their pointed tips) or fan shells (for the shell's fan-like or narrowly triangular shape). The shell is very thin and fragile, the hinge is toothless. The interior of the shell has a thin pearly layer towards the anterior half of the valves. The two adductor muscle scars are unequal, with the anterior one relatively small. There is no pallial sinus. The foot is long, conical and grooved. It has no siphon. These bivalves are usually half-buried in the sand/mud, anchored to their position by numerous byssal threads. The byssal threads of some pen shells are in fact used to weave into sea silk, a very valuable fabric which is extremely light and warm. Species found in the region are often collected for food.

Family Placunidae

Placunid bivalves (family Placunidae) are often called "window pane shells", as they are collected, polished, and pasted together to make into window panes or lamp shades in the region. The shells are very much flattened, and have a pearly surface. The hinge is almost straight with no teeth and no byssus. The ligament is usually internal, forming an inverted V-shaped structure. The shells have a single, centrally located posterior adductor muscle scar, and no pallial sinus. The foot is long, narrow and cylindrical.

Family Anomiidae

Anomiid bivalves (Family Anomiidae), or jingle shells, usually have very thin and somewhat flattened shells. They are usually attached to rocks, shell fragments, or even mangrove trees with their large and calcified byssus. There is a large and deep notch for the byssus in the lower valve near the hinge. The foot is dwarfed, finger-like, and grooved. Most shells have very pretty, pearly surfaces, and are hence collected for shellcraft.

Family Malleidae

Malleid bivalves (Family Malleidae) are called "hammer oysters", as the shells of many species appear "T"-shaped, though there are many exceptions. The hinge is narrow and held by an oblique ligament rather than teeth, and the shell is partially nacreous. The umbones are not conspicuous. The interior of each valve only has the posterior adductor muscle scar, and a pallial line without a sinus. The adults may or may not have byssal threads. The foot is divided into two unequal parts. They do not have a siphon. They can be free-living, partially buried in sandy substrates, or attached to hard substrates, or embedded in sponges.

Family Pteriidae

Pteriid bivalves (family Pteriidae) generally have somewhat compressed shells and a straight dorsal margin, with a wing-like ear on each or both ends. Members previously group under the family Isognomonidae (commonly called "leaf oysters") are recently included under this family after phylogenetic studies. The left valve of the shell is usually a little more inflated than the right valve, and there is a strong byssal notch anteriorly. The exterior surface of the shell often appears scaly or lamellate. The umbones are small, and the hinge is narrow and usually toothless. The interior of the shell is usually nacreous, with one large posterior adductor muscle scar and a pallial line but no sinus. The foot is small and grooved, with a strong byssus. They do not have any siphon. Many pearl oysters are from this family, and they have been exploited since ancient times for their ability to produce pearls. Some species may be confused with members of the previous family.

Family Mytilidae

Mussels (Family Mytilidae) generally have pear-shaped shells, and are attached to the substrates with strong byssus. Most are found on rocky and other hard substrates, but some have adapted to living in sandy or muddy substrates as well, with some species building nest covering huge areas of shallow sea beds. The hinge has no or reduced teeth, and the ligament is long and external. The interior of the shell is pearly. The anterior adductor muscle scar is small or sometimes absent in the adult, while the posterior adductor scar is large. The shell has a pallial line but without a sinus. The foot is long and grooved. The siphons are either very reduced or absent. Many species are economically important, being edible and abundant.

Family Gryphaeidae

Gryphaeid bivalves (Family Gryphaeidae) are often called "honeycomb oysters" because under a magnifying lens, the shell structure exhibits a honeycomb-like appearance. The shells, often irregularly shaped, can grow to huge sizes of about 30cm, and hence they are sometimes mistaken to be giant clams. Both valves are convex with large, irregular radial ribs, giving the opening on the ventral side a zigzag appearance. The hinge has no tooth. In the shell interior, there is only a large and rounded posterior adductor muscle scar placed closer to the hinge, but no anterior one. The pallial line is present, but the sinus is obscure to absent. They have no siphon. Some species are collect for food.

Family Ostreidae

Ostreid bivalves (family Ostreidae), also called the "true oysters", are commercially important around the world as food oysters. The shell is hard and often irregularly shaped, and cemented to the substrate by the left valve. The right valve usually appears more flattened, with a protruding fringe beyond the shell margin. The hinge has no tooth, and the shell interior is porcelaneous. It only has the posterior adductor muscle scar, generally, but unlike the previous family it is positioned nearer to the ventral side than to the hinge. It has a pallial line without a sinus, obscure to absent. The animal has no byssus, foot or siphon. Interestingly, both egg-bearing (oviparous) and larvae-bearing (larviparous) species can be found within the family. The larviparous species are able to change sex in the same individual, while the oviparous species may produce either more male or female gametes depending on the nutrients available or environmental temperature.

Family Spondylidae

Spondylid bivalves (family Spondylidae), commonly called "thorny oysters", are more closely related to scallops genetically. The shell is usually stout and very variable in shape, but all are cemented to substrate by the right valve, which is more convex than the left valve. The hinge has two strongly curved teeth and two deep sockets in each valve. The hinge line is straight, and often with a small ear on either side of the umbo. The ligament is mostly internal. The outer surface is usually brightly coloured and marked with numerous thin and spiny or scaly protrusions. The interior of the shell is porcelaneous. Spondylid bivalves have a single, rounded posterior adductor muscle scar, but lacks the anterior muscle scar. The pallial line is present, but without a sinus. The foot is reduced, and the siphon is absent. The adult lacks a byssus. Many species are collected for food.

References

- Abbott, R. T., 1991. Seashells of Southeast Asia. Graham Brash, Singapore. 145 pp.

- Anderson, L.C., and P. D. Roopnarine. 2003. Evolution and phylogenetic relationships among Neogene Corbulidae (Bivalvia; Myoidea) of tropical America. Journal of Paleontology, 77: 890-906.

- Bowling, B. 2012. Identification Guide to Marine Organisms of Texas. Retrieved Nov 25, 2012, from http://txmarspecies.tamug.edu.

- Bunje, P. 2001. The bivalvia. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved Nov 14, 2012, from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/bivalvia.php.

- Canapa et al. 2001. A molecular phylogeny of Heterodonta (Bivalvia) based on small ribosomal subunit RNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, Vol. 21, No. 1, October, pp. 156–161.

- Carpenter, K. E. & V. H. Niem (eds), 1998-2001. FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific. Volumes 1 to 6. FAO, Rome. pp. 1-4218.

- Carter, J. G. et al. 2011. A synoptical classification of the bivalvia (mollusca). Paleontological Contributions 4: 1‑47.

- Cox, L. R., N. D. Newell et al. 1969. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology: Part N. Mollusca 6. Bivalvia, Volume 2. The Geological Society of America, Inc. and The University of Kansas.

- Distel D.L., W. Morrill, N. MacLaren-Toussaint, D. Franks & J. Waterbury. 2003. Teredinibacter turnerae gen. nov., sp. nov., a dinitrogen-fixing, cellulolytic, endosymbiotic gamma-proteobacterium isolated from the gills of wood-boring molluscs (Bivalvia: Teredinidae). International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 52 (6): 2261–2269.

- Gladys Archerd Shell Collection at Washington State University Tri-Cities Natural History Museum. 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2012, from http://shells.tricity.wsu.edu/ArcherdShellCollection/ShellCollection.html.

- Lam, K. and B. Morton. 2004. The oysters of Hong Kong (Bivalvia: Ostreidae and Gryphaeidae). The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 52(1):11-28.

- Oliver, A. P. H., 2012. Philip's guide to seashells of the world. Philip's, London. 320 pp.

- Rogers, J. E., 1908. The Shell Book - A Popular Guide to a Knowledge of the Families of Living Molluscs, and an Aid to the identification of Shells Native and Foreign. Charles T. Branford Co., Publishers. Boston, Massachusetts. 485 pp.

- Sipe, A. R., A. E. Wilbur and S. C. Cary. 2000. Bacterial symbiont transmission in the wood-boring shipworm Bankia setacea (Bivalvia: Teredinidae). App. and Env. Microbiol. 66 (4): 1685-1691.

- Tan, K. S. & L. M. Chou, 2000. A guide to common seashells of Singapore. Singapore Science Centre, Singapore. 168 pp.

- Tan, S. K. & H. P. M. Woo, 2010. A preliminary checklist of the molluscs of Singapore. Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore, Singapore. 78 pp. Uploaded 02 June 2010.

- Tan, S. K. & R. K. H. Yeo, 2010. The intertidal molluscs of Pulau Semakau: preliminary results of “Project Semakau". Nature in Singapore, 3: 287–296.

- Tan, S. K., S. H. Tan & M. E. Y. Low, 2011. A reassessment of Verpa penis (Linnaeus, 1758) (Mollusca: Bivalvia: Clavagelloidea), a species presumed nationally extinct. Nature in Singapore 2011, 4: 5–8.

- Wong, H. W., 2009. The Mactridae of East Coast Park, Singapore. Nature in Singapore, 2: 283–296.

- World Register of Marine Species. 2012. Retrieved Nov 14, 2012, from http://www.marinespecies.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment